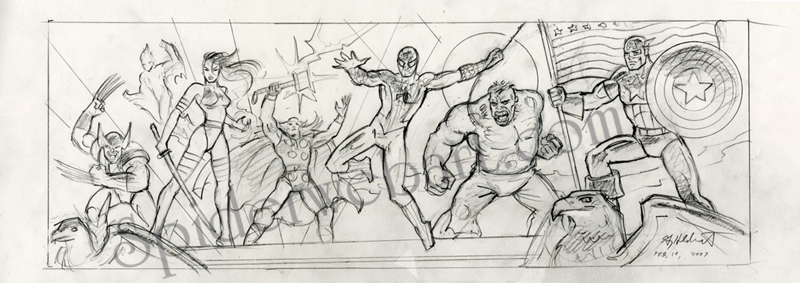

Marvel - Classic Characters Mural

DC - Classic Characters Mural

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON

THE MONTCLAIR ART MUSEUM

MONTCLAIR ART MUSEUM

3 South Mountain Avenue

Montclair, New Jersey 07042-1747

HERALD NEWS

By TIM NORRIS

Montclair exhibit details evolution of comic book superheroes

Friday, July 13, 2007

Up from the lake, over the roses, past stone-and-cinder parapets and under

a dragon's chin, Greg Hildebrandt steps with a visiting friend through

a chamber flanked in mythic beings and enormous animal skulls and into

his special room.

It's an "oh, wow!," "is this really...?," "look

at that!" kind of room, a sci-fi and fantasy fan's dream, and on

this recent evening, as fireflies dance above Lake Hopatcong in central

New Jersey's wooded hills, the friend, Michael Uslan, is oh-wowing and

snatching up an item that changed his life.

"Detective Comics, May, 1939!," he says, eyes wide, grin wider.

And he and Hildebrandt leap off into stories: how Hildebrandt, at age

5, crafted his first figure from an image of Disney's Pinocchio and went

on (with his identical twin, Tim) to build a giant squid in their basement

in Michigan and a giant reputation in fantasy art; how the Batman figure

on the cover of that 1939 comic book (in its first-ever appearance) and

also across Uslan's T-shirt that night, empowered Uslan to battle 13 years

for backing and finally produce the first, and then four more, Batman

movies.

"Oooh!" Uslan says, and he beams and points to an especially

rare issue from 1940: Will Eisner's "The Spirit." That series,

Uslan says, might be the greatest individual creative work in comic book

history. "Eisner invented a new language of story-telling,"

he says, "and he went on to create the graphic novel." "And,

here, look at this!" Hildebrandt says, lifting a "Captain America"

by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby and pointing to panel frames gone jagged and

sinuous. "They broke the frame like breaking the fourth wall,"

Uslan says.

The men can't help themselves. A shared passion for comic book stories

and characters, they say, involves finding and following dreams, tapping

the life force, overcoming fears, outlasting trouble. Now they are helping

to shape a new enterprise that lifts the comic book, long derided as low

art and once attacked for corrupting youth, into a realm of art and exhilaration.

"Reflecting Culture: The Evolution of American Comic Book Superheroes"

is set to open Saturday for a run through Jan. 13, 2008, at the Montclair

Art Museum (MAM). For young readers, collector-investors and scholars

alike, its array of vintage comic books, original sketches and drawings,

detailed notes and a host of films, promises pleasures for brain and glands.

Assembling more than 150 original drawings, comic books and graphic novels

from 1938 to the present drew Gail Stavitsky, the exhibition's curator

and chief curator for MAM, into a new world, one beyond normal art collectors,

institutions and dealers.

"This work is so intensely personal; it goes back to the childhoods

of the people involved," Stavitsky says. "They're easy to see

at first as being invented by men, appealing to male wish-fulfillment

fantasies and ideals, heroism, power, beautiful women. But I really did

change my feelings as I learned more. They transcend illustration. What

you'll see here really are examples of fine art."

The cultural reflection and evolution of comic books, a creation as purely

American as jazz, play among the museum's galleries. Brightly costumed,

athletic good guys (and the rare Wonder Woman) of DC and other comics,

fighting crime and social ills through the post-Depression New Deal and

then battling agents of the Axis powers through World War II, give way

to Marvel's more quirky and circumspect crime-fighters, wrestling with

their own faults and insecurities. More recent comic books venture into

even darker realms of human and social experience, into conformity and

racism, into genocide and global pollution, into politics and pop culture,

into sin and death and redemption.

Through it all, the exhibit's contributors say, scenes meticulously penciled,

inked and colored across myriad pages of superhero comic books deliver

almost unrelenting action and intimacy. The books are more than adjuncts

to movies or a child's introduction to books, the men say; they are a

unique visual and literary form, demanding writers and artists who can

grab an audience panel-by-panel and move a story energetically forward

across the white space between. In compelling that visual leap, Uslan

says, they invoke a power that TV and movies too often siphon off: imagination.

Uslan, 56, born in Cedar Grove and living now in Montclair, is a key contributor to the exhibit. His wife, Nancy, was first to suggest it to board member Susan Bershad, based on the Uslans' celebrated display at the University of Indiana in 2005. More than 35,000 of Uslan's comic books fill an archive in Indiana's Lilly Library, and comics and art from his world-class collections serve as one of the MAM exhibit's cornerstones.

Another cornerstone will come from Hildebrandt, a youthful 68. With his late brother, Tim, he is famed for book covers and posters, including Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" and a poster for "Star Wars" (Luke Skywalker thrusting a sword to the heavens, Princess Leia flashing a lot of leg) that still sells. His household's guardian dragon, a metal gargoyle above the front door of his Lake Hopatcong home, hints at Hildebrandt's trade: He is a fantasy illustrator of global renown, and the museum has commissioned him to paint two large-scale companion murals of comic book heroes, to be installed along the museum's back staircase and celebrated Sept. 16.

He and Uslan can chant those heroes' names in enthused unison: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Spectre, Green Lantern, Hawkman, the Joker and Lex Luthor from DC Comics, and the Marvel Comics legion, Captain America, the Sub Mariner, Human Torch, Dare Devil, Thor, the Green Goblin, Spider-Man.

Those were the allies of their dreams. This was the pre-and-post-World War II era called the Golden Age of comic books, when millions of American young people, mostly boys, began flocking to local stores to riffle through racks and spirit home the latest issues.

Hildebrandt has brainstormed the mural design, a bold group portrait arrayed on a city roof against a night sky, but he has yet to touch brush to canvas. No one present over his dinner table that night seems worried. Hildebrandt's own partner in business, derring-do, and home life, Jean Scrocco, has everything scheduled. She has booked another job for his work table at the moment, and he will immerse himself in superheroes and acrylic paint soon enough.

Immersion, an escape from rigmarole, from the dull and the threatening and the inadequate, is part of a comic book's charm. As the men and their partners testify, it isn't just young readers who lose themselves in fantasy. Even bent over finely detailed handwork that might seem tedious and solitary, many of the artists do, too. Hildebrandt says that, for him, drawing and painting are not an escape from life; they're central to it. "I never feel alone there," he says. Comic books are far more than escape ladders, though, Uslan says. They reflect society's conventions, fads, language and prejudices. And fascination with them can last a lifetime. "I can't tell you right now where my cell phone is, or my wallet," he says. "But name an issue and I can give you panels and page numbers."

Uslan's connection is intellectual Ð he has written or co-written more than a dozen volumes on comic books Ð and also emotional. Bob Kane (born Robert Kahn), creator of Batman, like Superman inventors Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster and other pioneers, are first- or second-generation immigrants, most from central Europe, many Jewish. They gravitated to a "low-brow" art that nobody else wanted, and their heroes are resolutely American, often showroom-muscled and lantern-jawed, fighting for democratic ideals, for fairness and freedom and what's good and right.

"The artists wanted, more than anything," Uslan says, "to be American, to have their part of the American dream."

Few know the field from adolescent, acquisitive and academic angles better than Uslan. As an undergraduate at Indiana, he proposed and then defended a first-ever college course in comic books. A skeptical dean dismissed them as "cheap entertainment for children," and Uslan responded by likening the story of Superman, cast adrift in space as an infant by his parents as his planet, Krypton, exploded behind him, to that of the Biblical Moses, spared the Pharaoh's sword when set adrift by his mother in a boat of reeds.

Uslan's memory of closing the deal spills out fully composed. Uslan, friends say, is a walking volume of references, anecdotes and historical detail, a lawyer and scholar and deal-maker so focused on making the next eloquent pitch for a passion or a project that he can leave home wearing one brown shoe and one black. ("It's OK," he said, when it happened a few years ago. "I have another pair like this at home.").

Hildebrandt is more ethereal. His passions flare beyond prediction, sometimes plunging him for weeks into a new idea. With an impending project, he says, what wells up first is terror, and he can feel closer to young readers facing the new and strange and unknown in their own lives.

The home where he and Jean Scrocco entertain the Uslans that night is emphatically a "his and hers," a decorative expression of their individual passions: Greg's assortment of plaster figures, Jean's resplendent gardens, Greg's CD illustrations for the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, Jean's exotic collection of animal bones.

At the moment, among other things, Uslan is helping to produce one more Batman movie and looking forward to October, when cartoon artist and "Sin City" director Frank Miller will start shooting "The Spirit," with Uslan as executive producer.

Eighty-year-old cartoon and graphic artist Joe Kubert, in fact, brings up the visual and artistic bond between comic books and filmed action. The greatest magic in comic books, he says, sparks in electrical leaps from one brain cell to another.

"When I saw Hal Foster's (newspaper comic strip) 'Tarzan'," he says, "those illustrations were absolutely alive to me. Foster had an incredible ability to take a series of still pictures, illustrations, and lacing them together so they gave the impression of movement. I wasn't sitting apart, looking at something on paper. I was IN the trees, watching Tarzan go by!"

Life, of course, goes by, too, and also intrudes, as Uslan and Hildebrandt have learned. Across the table at Lake Hopatcong that recent night, the two couples talk, among other things, about enduring. They have all seen each other through losses, through Michael's with a film epic where one executive's departure from a movie studio killed a project he had worked on for three years; through Hildebrandt's long struggle, so far futile, to bring, Urshurak, to the screen.

The artist's great loss came last year: his twin brother, Tim, died of a brain hemorrhage caused by a fall related to low blood sugar. Though the twins were born identical, Tim inherited the family diabetes and Greg didn't. Life doesn't play fair or favorites, the men acknowledge, and friends help to keep them looking forward.

A superhero, now more often flawed and conflicted, they say, and the artist who draws the hero, and the client or producer who pays the bills, and the store or gallery that gives the hero a showing, and, especially, the fans who put their hearts into the stories, can help them through.

For more on Greg Hildebrandt and his art, look online at www.spiderwebart.com and www.brothershildebrandt.com.

Tim Norris